On April 1st, the City of Shanghai was called into a mandatory lockdown due to the rising number of positive COVID-19 cases. The lockdown was announced from April 1st – April 5th. In the days leading up to the lockdown, stores became overcrowded as people panic-purchased supplies to weather the lockdown storm. Within days, shelves were empty as people hoarded all they could. To make matters worse, the increasingly stringent policies restricted inbound goods from entering the city, thus leading to food and supply shortages for several weeks. To remedy this problem, the government promised food subsidies would be distributed to communities across the city as a supplement.

The initial days of lockdown were characterized by an eerie silence not experienced before in such a usually bustling city. There was no movement. No cars, no bikes, no pedestrians. The only time people were permitted outside of their apartment unit was for a mandatory PCR test, where the results were connected to your digital ID through various apps for contact tracing. All hoped this would be a short-lived experience. Everyone was wrong. In the evening of April 4th, it was announced that the lockdown would be extended indefinitely.

Sometime around April 15th I tested positive for COVID-19 through an at-home antigen test. It was later confirmed through a PCR test that I indeed had the virus. I don’t know how I contracted it, considering I had been home for two weeks. The accepted theory between friends and I is that I contracted the virus while getting test for the virus, oh the cruel irony. The major symptoms I felt were that of a sore throat, headache, fatigue, and generally sense of malaise. I felt as though I were poisoned and knew immediately this was no regular cold. Within a few days I had overcome the major symptoms and was on the mend. The only problem was that I was already identified as someone with the virus and on a list to be sent to a quarantine facility due to the contact tracing apps. My fate was sealed.

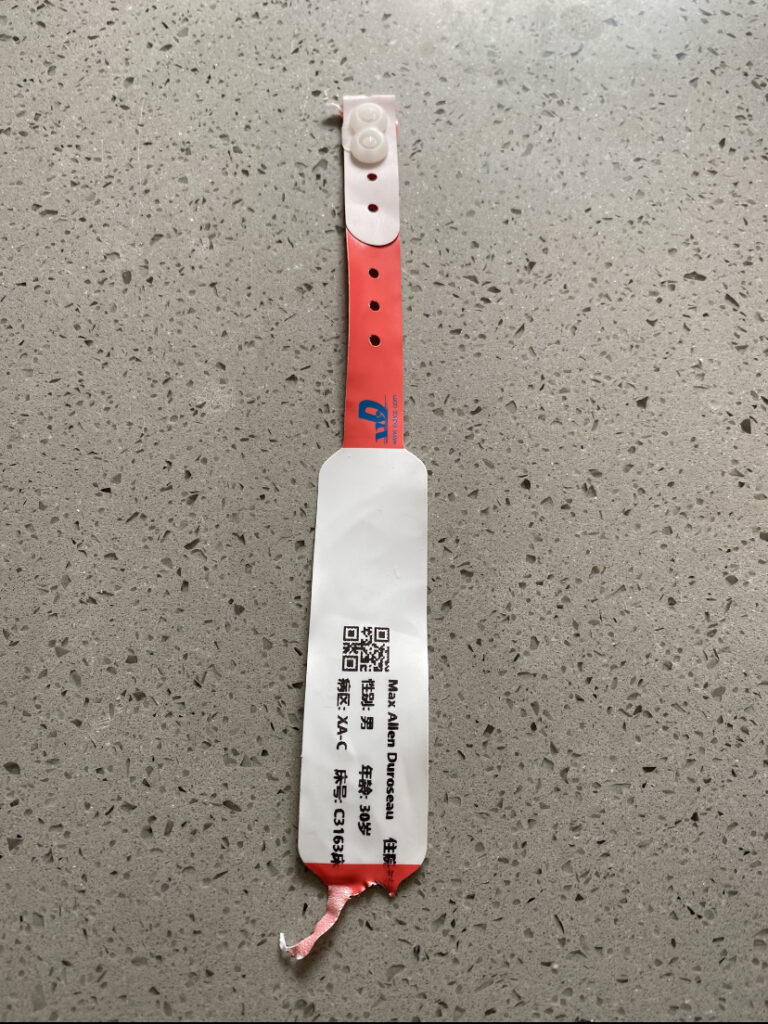

On April 21st I was sent to quarantine (方舱) after testing positive 6 days prior. I got the dreaded phone call that I would be picked up and taken away for isolation. I was sent to a facility called Bai Mao, which was previously a soap factory. Apparently, it was renovated in under 3 days to accommodate COVID patients. While the first few days were emotionally challenging, I was able to document some of my experience. One of the positive parts of the experience was that I was able to walk outside and enjoy the fresh air. A few of us even turned the green area into a workout space. Being outside became a type of escape from our very unwanted circumstance.

Every day at 2pm we would be given a PCR test. In order to be released from quarantine we would need to test negative two consecutive days in a row.

One of the prominent parts of being in quarantine was being constantly surrounded by hazmat volunteers. They were the first people you encountered when you arrived, they sprayed your belongings with a solution, directed you to your room, and provided important schedule updates.

On April 21st I was sent to quarantine (方舱) after testing positive 6 days prior. I got the dreaded phone call that I would be picked up and taken away for isolation. I was sent to a facility called Bai Mao, which was previously a soap factory. Apparently, it was renovated in under 3 days to accommodate COVID patients. While the first few days were emotionally challenging, I was able to document some of my experience. One of the positive parts of the experience was that I was able to walk outside and enjoy the fresh air. A few of us even turned the green area into a workout space. Being outside became a type of escape from our very unwanted circumstance.

Every day at 2pm we would be given a PCR test. In order to be released from quarantine we would need to test negative two consecutive days in a row.

One of the prominent parts of being in quarantine was being constantly surrounded by hazmat volunteers. They were the first people you encountered when you arrived, they sprayed your belongings with a solution, directed you to your room, and provided important schedule updates.

At first, most of my concern was for myself and the other patients. Over time however, I began to realize how this situation also affected the volunteers. They worked long hours, wore the protection suit despite poor air circulation, and had to serve those in isolation constantly. I could see the work was taking a toll on them mentally, as they bore the complaints of all around them. I began to feel sympathy and a hint of gratitude for their work.

Because of them I did not have to worry about food 3X a day. I was offered medication and tested regularly. While much was left to be desired in terms of organization, they did their best. They were people just like us trying to cope with a difficult situation. Often, we lost sight of that.

While only one volunteer was unpleasant (he called me a racial slur), most were pleasant and friendly.

The image above was taken on the last day of being at this facility. I got up early to capture it before too many people were outside. I wanted to remember this place. While many people would want to quickly forget these experiences, I believe it’s important to document pivotal moments in our story. This was so I could remember the lessons I’ve learned.

For me, I learned that the simple things in life are what we need during difficult times. While outside, I sat with other COVID patients and commiserated over our condition. We discussed many things and got to know one another. We shared silences as well as laughter. We were each other’s safe space.

I spent a total of 10 days there.

Unfortunately, due to a passport mix-up, I was not permitted to go home (although I was now testing negative for COVID). I was then transferred from the Bai Mao facility, where I shared a room with one roommate, and could freely walk outside to a giant warehouse on the West Bund with no privacy.

Here, the washrooms were all outside in the form of porte-potties. We were in close proximity to other infected patients and could not control social distancing. The environment was very noisy. The lights NEVER turned off. NEVER.

At this point, many of the patients coming from the Bai Mao facility (including myself) either sank into a depression or became numb. We were confused as to why we were transferred, and many people chose to deal with their emotions in different ways. Some people grew silent as they adjusted to their new environment. Others turned to distractions. One person refused to get up from their bed until it was time to leave. I chose to continue documenting what was happening around me. This was how I would cope with what seemed like an endless imprisonment.

What started out as a way of keeping myself busy soon became a project that stirred passion within me. I was moved by the beautiful faces I saw in quarantine. The vulnerability, the frustration, the acceptance. All of it was a showcase of the human spirit and a case study on resilience.

My favorite part of this process was disappearing behind the camera. I allowed my thoughts, emotions, and inner protest to melt into nothing. The only person that mattered was the one right in front of me. And it made me feel free. I was no longer bound by the chains of isolation and could now connect with those who fell within my creative gaze. I saw them. I felt them. I was them.

I suppose the true lesson is that when we take a moment to stop worrying solely about ourselves, we can begin to live in a way that’s full and free from the cares of this life.

In those times I wished my Chinese had been better. I would’ve asked the workers how they were doing. What they were feeling.

If I had to guess, it would’ve been a sense of duty to serve their countrymen. A feeling of pride that they rose to the occasion. Some exhaustion from the long hours and being away from their comforts. And finally, burnout.

These volunteers treated us foreigners quite well. They seemed to enjoy seeing new faces and welcomed me taking their pictures.

I feel like they wanted someone to document their sacrifice. To remember their courage and bravery. To not forget what they did.

I felt this was an honorable request, even if it was never made out loud.

On May 3rd, I was released from quarantine. I walked down what was normally a heavily crowded street to get to my apartment. There was a barrenness that I wasn’t accustomed to.

I felt the shift in the city. So many foreigners I’ve spoken to have shared their thoughts for the future, and whether they saw themselves continuing to be expats here.

I believe a mass exodus is on the horizon and these events that have taken place will serve as the catalyst.

It is yet to be seen what long-term effects will come of all this. Hopefully things won’t become too unrecognizable.

My feelings upon return home were complicated. Being able to sleep in my own bed (with the lights off) was amazing. Not to mention showering in my own bathroom! And even having access to all my possessions was great.

But while I was happy to be home, I was also sad. I took the liberty of calling those feelings: Post-quarantine Blues!

Stepping into my apartment for the first time felt unfamiliar. After 12 days away, I didn’t know how to adjust to being back in my place. I think it’s because I couldn’t shake the feeling that anyone could come to my door and remove me again. There was a sense of angst that was inescapable. The reality that my place in China was impermanent never felt so apparent.

My good friend also joked that I was institutionalized! Although he was being light, there may have been truth to it.

I will never forget my time in quarantine. It has given me such fresh perspective on my life, as well as the World around me, and is an experience I’ll carry for the rest of my life.

What a time to be alive.

-Max

0 Comments